In September I was fortunate to attend the excellent Future of Wild Europe conference at Leeds University. Over three days, keynote speakers and early-career researchers in the environmental humanities gave presentations on rewilding, ethnography and many other fascinating topics related to political ecology.

Pretty much my first academic conference, I found it hugely stimulating, and a great opportunity to accost authors of papers I was citing in my dissertation at coffee break. It was also not without a share of controversy and a range of different and at times conflicting visions were presented as to what a “wild Europe” might mean and how to get there.

Irma Allen of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm also attended the conference and has written about her impressions in a thought-provoking blog, The Trouble with Rewilding. Here, she poses some challenging questions about what she felt was revealed concerning the ideological underpinnings of the rewilding movement. Three main issues concern her: the racialized Malthussian origins of rewilding; concerns about land abandonment and passive rewilding in Europe being facilitated by importing “virtual” agricultural land; and rewilding initiatives being concentrated in the historically marginalized regions of Central and Eastern Europe.

-

Malthus and the discourse of over-population

Environmentalism has a dark history of Malthussian “Limits to Growth” thinking and misanthropy. A focus on and at times pre-occupation with over-population as the primary driver of environmental destruction, frequently accompanied by the reification of a sublime Nature above human well-being, has lead to an assumption that the only truly healthy Nature is one devoid of humans.

As Allen says, this issue was most famously addressed by William Cronon in his 1996 essay The Trouble with Wilderness (pdf)(Cronon 1996):

Perhaps partly because our own conflicts over such places and organisms have become so messy, the convergence of wilderness values with concerns about biological diversity and endangered species has helped produce a deep fascination for remote ecosystems, where it is easier to imagine that nature might somehow be “left alone” to flourish by its own pristine devices. The classic example is the tropical rain forest, which since the 1970s has become the most powerful modern icon of unfallen, sacred land—a veritable Garden of Eden—for many Americans and Europeans. And yet protecting the rain forest in the eyes of First World environmnetalists all too often means protecting it from people who live there.

Those who seek to preserve such “wilderness” from the activities of native peoples run the risk of reproducing the same tragedy—being forceably removed from an ancient home—that befell American Indians. Third World countries face massive environmental problems and deep social conflicts, but these are not likely to be solved by a cultural myth that encourages us to “preserve” peopleless landscapes that have not existed in such places for millennia…

…exporting American notions of wilderness in this way can become an unthinking and self-defeating form of cultural imperialism

Cronon goes onto argue that the dichotomy that the concept of wilderness creates- that of a separation of anything touched by humans from pristine Nature- leads us to de-value the more prosaic world that we inhabit, and thus disregard the nature and the natural that is all around us, in our backyards, or even in the heart of the city. If we hold an essentially illusory image of “the wilderness”- since nature untouched by humans hardly exists anymore, and arguably has not for a long time- as the only true nature worth preserving or paying attention to, we will neglect to look after the less exciting but equally important diversity than can often be found all around us.

In her post, Allen goes onto trace these Malthussian strains from one of the originators of rewilding, deep ecologist Dave Foreman, to the founder of Rewilding Europe, Toby Aykroyd, who also gave a presentation at the Leeds conference. Allen found that Aykroyd is also the founder of the Population and Sustainability Network, which focusses on the links between reproductive health, population and the environment, and provides free family planning services in developing countries- all well and good she says, but “when motivated by concern over natural resources and carrying capacities, and linked to power-laden development agendas, this shades into murkier territories and rationales that I find deeply uncomfortable.”

In my dissertation on rewilding (available here) I also referenced some of these associations:

The darker side of misanthropic environmentalism still pervades more extreme rewilding discourses and can readily be found on online forums and blogs (see for example The Happy Anachronism blog, 2012; The Rewild West n.d.). Drastic reductions in human population, either forced or through some kind of ecological collapse, are seen by these writers as a necessary and even desirable pre-requisite to any genuine rewilding (Foreman 2015). At times, these views can seem uncomfortably close to certain strands of Nazi ideology, which was itself strongly informed by belief in the purity of pristine Nature, underpinned by their mythology of the urwald (primeval forest) which they associated with the Fatherland and Aryan supremacy (Biehl and Staudenmaier 1995; Schama 1996).

While some find thinking about this uncomfortable and would rather not have it discussed, or claim that it is no longer relevant, the conservation movement needs to own openly to its origins in a history of forced evictions of native peoples in order to create protected wilderness areas (Dowie 2011), a practice that is still going on today.

In this way, “wilderness” can be seen a cultural artifact, literally created by the forced removal of people (Ginn and Demeritt 2008). This is what Monbiot (1994) calls forced rewilding (it is a curious aspect of his work that he gives scant mention of these issues in his more recent influential rewilding book Feral [2013]).

Perhaps oddly, neither Allen in her post, nor as far as I could see from a quick search on the PSN website, make any mention of the demographic transition- the well researched process of development, by which birth rates decline, sometimes dramatically, with economic development, as infant mortality declines and people move away from subsistence farming, and no longer require large numbers of children to ensure enough survived to work the land (Galor and Weil 2000).

Given that the data has been in on this process for decades and just keeps getting stronger, psychological explanations are being employed, as referenced by Allen, to explain why overpopulation is still routinely referred to as “the elephant on the room”, a kind of “public secret” when in fact it has always been a core underpinning of the environmental movement, championed most prominently by Stanford professor Paul Ehrlich (1968). A challenge for rewilding then will be to make a clean break with such Malthussian ideology.

Dolly Jørgensen, who also spoke at the conference, comes to the same conclusion in her review of rewilding:

Taken as a whole, rewilding discourse seeks to erase human history and involvement with the land and flora and fauna

(Jørgensen, D. 2014)

In response, Prior and Ward (2016) make the case that many rewilding “experiments” are indeed well integrated with human activity and presence, citing two examples of beaver re-introductions in Scotland, and the Oostvaardersplassen reserve in the Netherlands. However, my own research last summer suggests that people are likely to continue to use “rewilding” in many different ways, and even if efforts are made to shake off the idea of rewilding being about the reconstruction of an imagined “pristine” nature, there is bound to be some considerable slippage in public discourse. Rewilding will remain strongly associated with wilderness discourse and continue to draw from a broad church, including Malthussian deep-ecology.

Rather than focus on over-population, Allen sees over-consumption as being a more significant issue, bringing her to her second issue: exporting productive land overseas to allow increased conservation at home.

2. Virtual land trade in Europe

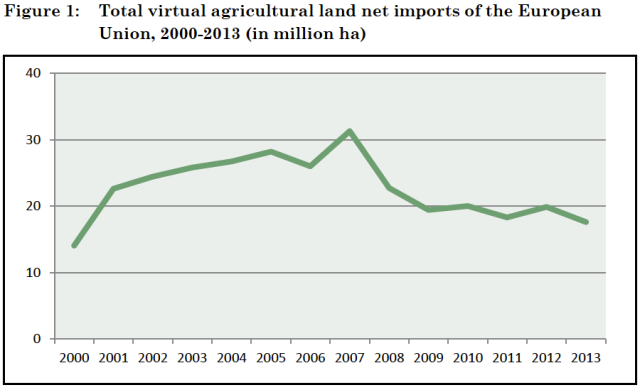

Citing the 2010 OPERA report (von Witzke and Noleppa 2010) on land-sparing, Allen points to data suggesting that Europe’s dramatic increase in productive land abandonment- hailed by some as an opportunity for passive rewilding ( Navarro and Pereira 2012) and regreening (the topic of my last post) has come only at the expense of a “virtual land grab” outside the EU, mainly in developing countries, who have seen a consummate loss of forest cover. If so, this would provide a challenge to those, like myself, who have argued for intensification of agriculture as a way of freeing up farmland for nature.

However more recent data show that post-2008, the trend within the EU of increasing its virtual land imports has reversed, declining more than a third from the peak of 2007/8:

Source: Noleppa, S., & Cartsburg, M. (2014). Another look at agricultural trade of the European Union: Virtual land trade and self-sufficiency. Hffa Research.

While Europe still imports a large amount of “virtual farmlandland”, mainly in the form of oilseed crops, primarily soya from South America, the trend for other crops is in the other direction as Europe increases efficiency and raises yields. Moreover, a proportion of this virtual acreage is for the production of crops to meet the EU biofuel mandates. Under scenarios explored in the earlier study, this could already account for some 3-4m ha, rising by another 10% if biofuel mandates are increased.

Allen also points to the issue of land-grabbing in Europe, fingering EU-backed neo-liberal policies. While this may be a serious problem, dislocating traditional farming communities, this cannot be the same land that is being abandoned, but is rather for intensive production- which itself could lead to more abandonment of marginal land and subsequent re-greening. Implicit in her post is also a degree of “anti-capitalist” rhetoric, which ignores the considerable data for overall long-term improvement of living conditions under capitalism.

Allen argues that rather than welcoming the process of depopulating rural areas and land abandonment, rewilding should align itself with High Nature Value farming (HNV) and the benefits known to be provided to wildlife by by small farms- in other words, a land-sharing approach:

The key point here is that there is nothing neutral about processes of rural depopulation. Rather than passively celebrate their demise, should rewilding advocates not align themselves with small-scale farmers, whose practices, at least in Europe, can often encourage far greater biodiversity, and are themselves perhaps part of the very notion of ‘wild’ we might want to cultivate – non-homogenous, diverse, non-standardised, and self-willed?

This does seem to obviate the whole point of what rewilding seeks to achieve: If rewilding means anything at all distinctive, it is as a challenge to conventional conservation policies, which are deeply meshed within agri-environment schemes coming out of Europe the past 40 years. In contrast to rewilding, whereby natural processes are given priority to lead where they may (not unproblematic in itself), HNV farming has more in common with what we already have, which seeks to maintain specific habitats, generally those found in pre-WW2 pre-industrially farmed landscapes.

Agri-environment policies are already geared to promote land-sharing. But with world food demand set to rise dramatically over the coming decades, we will also need land-sparing, including new technologies to increase yields. A stalling in innovation is cited as one of the major reasons for the slow-down in agricultural yield increases globally, and in Europe especially, where GMOs for example are strongly opposed and largely restricted. The OPERA report concludes that excessive regulations and bureaucracy have stifled agricultural innovation in the EU, while an increase in lower-yielding Organic agriculture across the EU would only lead to in an increase in virtual land imports.

3. Bio-capitalism in Eastern Europe

Allen’s final point is to question how, although rewilding generally has been focussed on the developed world, yet within Europe, most initiatives seem to be in the poorer eastern countries. This is true at least for one of the more prominent rewilding organisations, Rewilding Europe, which has most of its projects located in the poorer European countries of eastern Europe.

I think this is another valid point which is worthy of further discussion and research. This could be focussed for example on how eastern Europe may be at an earlier stage of the demographic transition through which more devloped countries have already passed, and how this relates to forest transitions. From informal discussions and other presentations at the Leeds conference, there were suggestions that RW Europe, and perhaps other organisations, see the depopulation of rural areas much to their advantage, and their assumption that alternative livelihoods in eco- and wildlife tourism can seemlessly make up for the decline in farming in these areas needs to be demonstrated rather than assumed.

Conclusion

Irma Allen has raised some perhaps uncomfortable questions for the rewilding movement. Its Malthussian origins should not be ignored and vigilance is needed to ensure it just does not become just the latest vehicle for misanthropic green fascism. Nevertheless, there are some contradictions in her arguments, and a danger of replicating these very same issues in her own apparent preference for small farms and extensive agriculture, while opposing agricultural technology that is badly needed to feed a still growing world population aswell as freeing up more land for nature. This is not to undersate the social disruptions which are likely to accompany such transitions, and further study should be undertaken to assess the social impacts of both agricultural intensification and any possible “green-grabbing” being carried out in the name of rewilding.

References

Biehl, J. and Staudenmaier, P. 1995 Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience AK

Press

Cronon, W. (ed) 1996 Uncommon Ground- Rethinking the Human Place in Nature

W.W.Norton & Co. New York/London

Ehrlich, P. 1968 The Population Bomb MacMillan

FAO. 2016. State of the World’s Forests 2016.

Forests and agriculture: land-use challenges and opportunities. Rome.

Foreman, D. 2015 [online] An Interview with Dave Foreman

http://www.thewildernist.org/2015/03/interview-dave-foreman/ [last accessed 12-07-2016]

Galor, O. and Weil, D.N. 2000 Population, Technology and Growth: From Malthusian Stagnation to the Demographic Transition and Beyond American Economic Review Vol. 90, No. 4 (Sept 2000), pp 806-828

Ginn, F. and Demeritt, D. 2008 Nature: A Contested Concept Ch.17 in Clifford, N.J. et al 2008 Key Concepts in Geography, Sage Publications Ltd.

Jørgensen, D. 2014 Rethinking Rewilding Geoforum 65 (2015) 482–488

Monbiot 1994 No Man’s Land: an investigative journey Through Kenya and Tanzania

MacMillan, London

Monbiot, G. 2013 Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life Allen Lane

Navarro, L.M. and Pereira, H. M.2012 Rewilding Abandoned landscapes in Europe Ecosystems (2012) 15: 900–912

Noleppa, S., & Cartsburg, M. (2014). Another look at agricultural trade of the European Union: Virtual land trade and self-sufficiency. Hffa Research.

Prior, J. and Ward, K. 2016 Rethinking rewilding: A response to Jørgensen Geoforum 69

(2016) 132–135

Schama, S. (1996), S. 1996 Landscape and Memory Vintage

Von Witzke, H., & Noleppa, S. (2010). EU agricultural production and trade: Can more efficiency prevent increasing “land-grabbing”outside of Europe? Study Commissioned by OPERA.

Photos: Bialowiezça forest, Graham Strouts 2013

Photos: Bialowiezça forest, Graham Strouts 2013

Above- larch stand due for sanitation felling

Above- larch stand due for sanitation felling